How a Woman Who Was Never Meant To Be Seen Fooled the U.S. President and Saved Nations

She walked into the Oval Office wearing someone else’s face. Not a metaphor—a mask so flawless it fooled President George H.W. Bush until she peeled it away in silence. For decades, Jonna Mendez had operated in the shadows of American intelligence, mastering the art of vanishing in broad daylight, crafting second identities that slipped agents past assassins, traitors, and entire regimes. She was a mother, a spy, and the CIA’s Chief of Disguise. But beneath the latex, the secrets, and the silence, Mendez carried something far more dangerous than deception, and it’s the truth that no man could ever prepare himself for.

The Mask That Fooled the White House

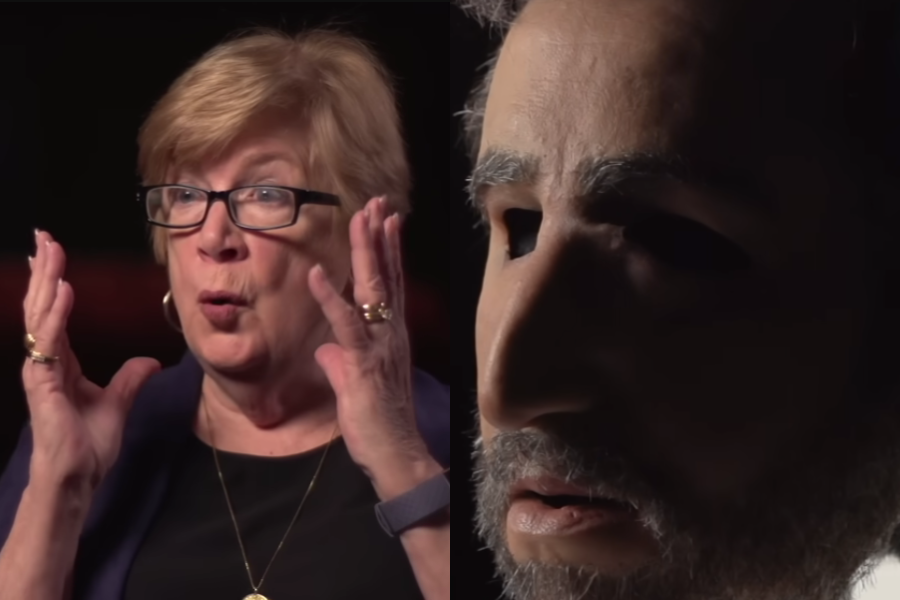

On February 4, 1993, Jonna Mendez entered the Oval Office wearing someone else’s face. To the room, she was just another mid-level analyst, but younger and more charming.

“You might remember these?” she asked President George H.W. Bush, showing him photographs of the disguises they had made for missions. “I’m here to show you the next level.”

Then the President leaned backwards and said confidently, “So, show me.” Mendez wearing her grin, “I’m already wearing it.” John Sununu who was with them almost fell from his chair, witnessing the disguise unveiled in front of him, “Holy smokes…”

A Woman in a Man’s World

When Mendez joined the CIA in 1966, women were mostly relegated to secretarial work or administrative “support” roles. She recalled, “I was brought in as a GS-4, the lowest rank.”

Despite the institutional barriers, she advanced, not through favoritism, but field expertise. “There was no roadmap,” Mendez told The Washington Post in 2019. “You just did the job better than everyone else.”

She didn’t ask for special treatment. She asked for training, clearance, and opportunity. And when denied, she quietly outperformed expectations until there was no denying her place in rooms where decisions—and history—were made. But she wasn’t finished breaking rules yet.

Training in Secrets

At the CIA’s Office of Technical Services, Mendez underwent the same grueling tests as her male counterparts. She learned surveillance evasion, brush-pass techniques, and how to vanish in foreign cities.

“They once left me in downtown D.C. and told me to get back without being followed,” she told the Los Angeles Times. “It was terrifying—but that was the point.”

Training was more than tactical—it was psychological. Disguise, she learned, wasn’t about hiding your face. It was about becoming invisible by choice. Her early training shaped everything that came next, especially the assignments where lives—not promotions—were on the line.

Kansas to Langley

Jonna Mendez was born Jonna Hiestand in Wichita, Kansas, in 1945. Her upbringing was quiet, stable, and Midwestern. “I didn’t dream of being a spy,” she told NPR in 2019. “It found me.”

She met Tony Mendez, already a CIA officer, while working for a defense contractor in Europe. “I thought, ‘Oh my God, he has the coolest job in the world,’” she said in an interview for the International Spy Museum.

After marrying Tony, she joined the CIA herself, starting with entry-level work. “They called it the typing pool,” she recalled. “But I watched everything. I was studying—quietly—how this world worked.”

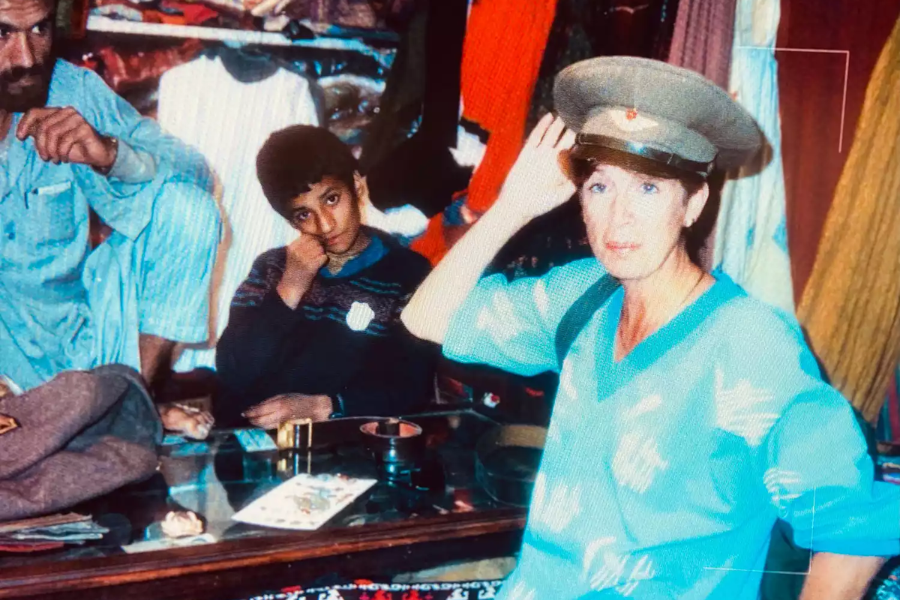

Moscow Rules

Mendez’s work eventually placed her at the heart of one of the Cold War’s most perilous theaters: Moscow. “It was the most hostile operating environment we had,” she wrote in The Moscow Rules, co-authored with Tony Mendez.

In that city, U.S. operatives were constantly surveilled. “You couldn’t scratch your ear without being noticed,” she explained in a 2019 60 Minutes segment. Agents needed disguises that could withstand military scrutiny and execute under pressure.

The CIA developed what became known as the “Moscow Rules”—a list of unwritten protocols for survival. Mendez didn’t just follow them—she engineered the illusions that made them viable.

The Art of Disguise

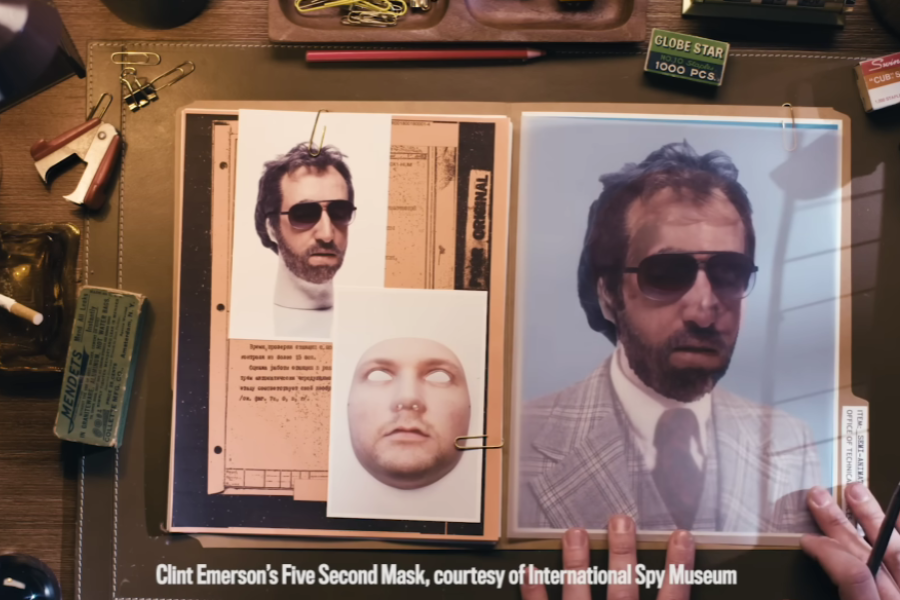

Within the CIA’s Office of Technical Services, Mendez led innovations that blurred the line between reality and artifice. “We were building masks that could pass within inches,” she told The New York Times.

These were not Halloween masks. They were full-face prosthetics, hyper-realistic, equipped with breathing channels, blinking eyelids, and even skin textures that fooled close inspection. “It had to hold up during surveillance,” she said. “If the eyes looked wrong, it could mean death.”

Her disguises gave agents new lives—and safe exits. “You weren’t just changing appearance,” she said in a Spy Museum interview. “You were creating a whole person.”

Marriage Undercover

Jonna and Tony Mendez were an anomaly: two CIA officers married to each other, both experts in disguise. Their lives were split between parenting, tradecraft, and compartmentalized secrets.

“There were parts of our work we couldn’t even share with each other,” Jonna said in an interview with HistoryNet. “Compartmentalization was a rule, even in marriage.”

Still, they were bonded by mission and trust. “You didn’t have to explain why you couldn’t talk about something,” she said. “We just understood. We were trained not to ask.” But secrecy didn’t stop where the front door ended.

Spy Games and Motherhood

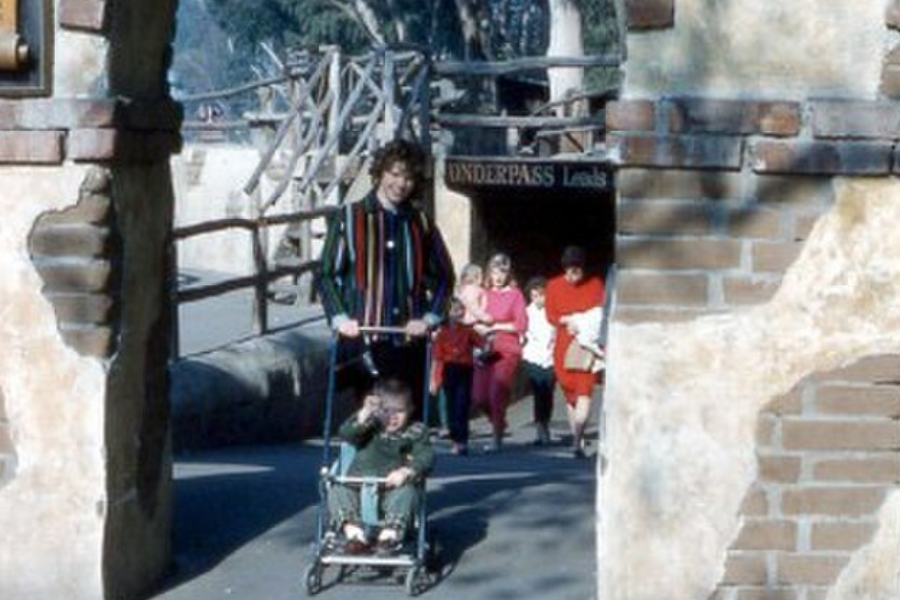

Raising a child while serving undercover required precision. “Our son didn’t know what we did,” Jonna explained to the Spy Museum. “He thought Tony worked in fine arts, and I did photography.”

The lines blurred. “I once had to change into a disguise in a McDonald’s bathroom, with my son outside the stall,” she told CBS This Morning. “He just thought Mom wore weird wigs.”

She wasn’t trying to be a hero. “You figure it out,” she said plainly. “You show up at the drop site. Then you show up for the parent-teacher conference.” But some nights were far from normal.

A Glimpse of Death

One mission in a hostile capital tested every lesson she’d ever learned. Surveillance teams circled. A routine brush pass turned tense when a local agent stared too long, too knowingly.

“I knew something was wrong,” she said in a 2020 C-SPAN appearance. “You feel it in your gut before you see it in their eyes.” Her disguise, she feared, had a flaw.

She adjusted her posture, changed her pace, and entered a shop. He didn’t follow. “One blink too long, and I’m caught,” she said. “There’s no cavalry coming. You’re your own backup.” That night, she didn’t sleep.

Lessons from Antonio

Tony Mendez was already a legend at Langley when Argo—the operation and the movie—made his story public. But at home, he was still Jonna’s partner and peer.

“We had a very competitive relationship,” Jonna told the Spy Museum. “If I built a mask, he’d try to break it. If he fooled me, I had to outdo him next time.”

Their partnership was both personal and professional. “Tony taught me that disguise is more about psychology than props,” she said in a 2019 C-SPAN interview. “You have to become the lie to sell it.” And now, she was in charge.

Inside the Disguise Lab

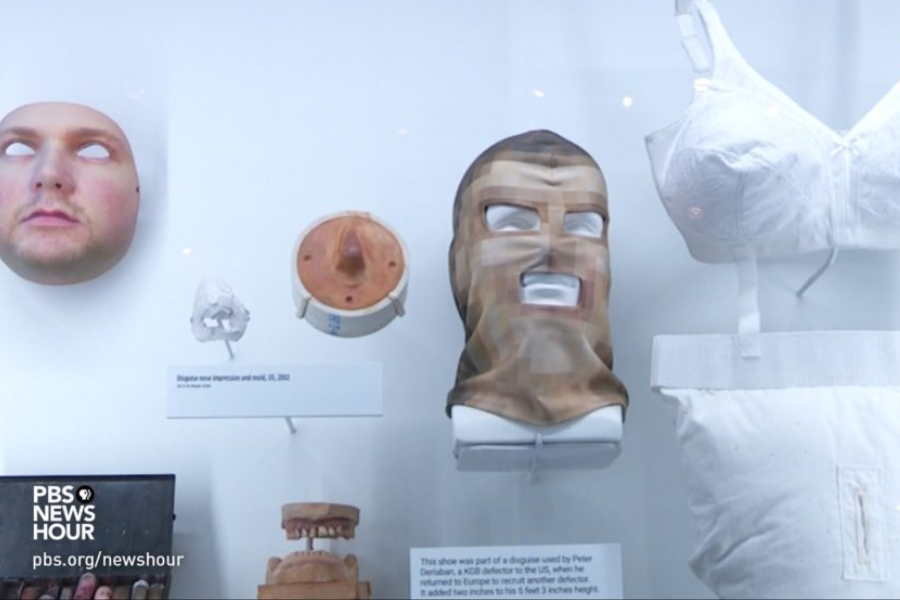

Inside the CIA’s disguise lab, the shelves were lined with latex masks, synthetic hair, voice modulators, and skin-safe adhesives. “It looked like Hollywood,” Jonna recalled in her memoir The Moscow Rules.

But this wasn’t cinema—it was survival. “The goal wasn’t to look disguised,” she told The New York Times. “It was to look normal. So normal you disappeared into a crowd.”

She led innovations in mask design, portable disguise kits, and full-body doubles. “We were creating illusions under combat conditions,” she said. “You didn’t have time for a mirror. You had seconds.” And failure could be fatal.

The Making of a Legend

As Chief of Disguise, Mendez wasn’t just managing materials—she was rewriting methodology. Her work helped shape the modern CIA’s human intelligence and agent protection approach.

“She was the person we all went to when we needed something to work,” said a former CIA officer in a Washingtonian profile. “She didn’t say no. She made it happen.”

But her quiet competence didn’t go unnoticed. “There was a glass ceiling,” she said. “But I didn’t shatter it. I climbed around it.” Her rise wasn’t dramatic, but it was undeniable. And her disguises were saving lives.

The Double Life at Langley

Jonna’s days began like any federal worker’s: badge swipe, elevator ride, office desk. But behind her file folders were blueprints for deception that saved lives across continents.

“I spent a lot of time invisible—by design,” she said during a Spy Museum panel. “You don’t need to be loud when your work speaks for itself.”

At Langley, she led without theatrics. “The Chief of Disguise was expected to be male, brash, field-tough,” she recalled. “I didn’t fit that mold. So I redefined it.” Meanwhile, her illusions went global—and deadly serious.

Global Chessboard

The Cold War played out not just in war rooms, but in alleys, cafes, embassies—anywhere information changed hands. Mendez’s disguises were deployed in Havana, Moscow, and East Berlin.

“We had to make our people unremarkable,” she told 60 Minutes. “That’s harder than making someone disappear. It’s making them fade—on purpose.” Her disguises worked in seconds, under pressure.

She never traveled with her name on paper. “I used aliases that didn’t even belong to me,” she said. “But if the illusion worked, no one ever asked.” Then came a case that tested every principle she taught.

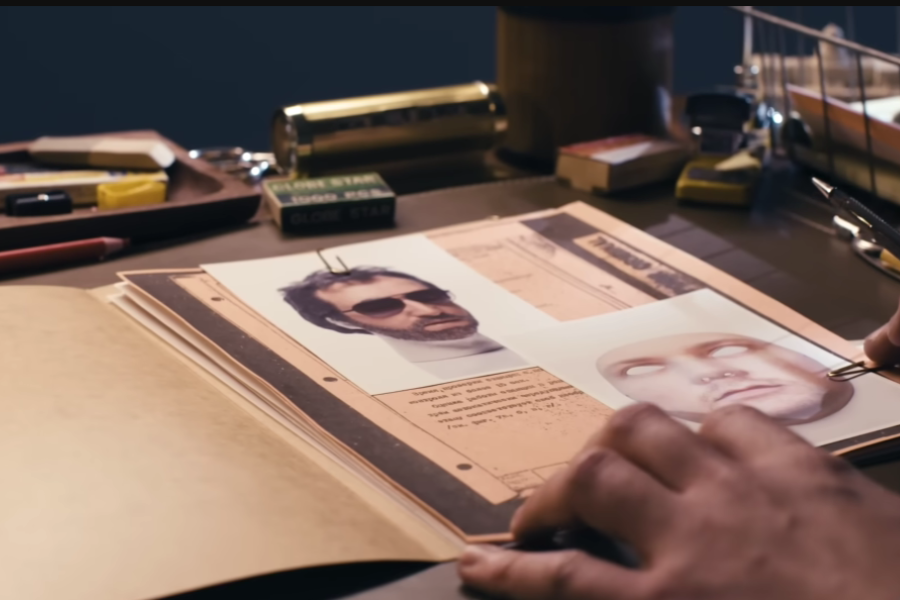

The Agent Who Vanished

In East Berlin, a CIA officer used one of Jonna’s new-generation disguise kits—a full-face mask, gait-adjusting inserts, and a simple trick: carry yourself like you belong.

“He entered as one person and exited as another,” Jonna explained in The Moscow Rules. The surveillance footage—later reviewed at Langley—showed no recognition, no suspicion.

“The disguise didn’t just protect him,” she said. “It protected the source who gave us intelligence. That’s what mattered most.” The agent returned safely. But not unchanged. “They said it was the first time they truly felt untouchable,” she recalled.

The Job Offer She Never Expected

She wasn’t gunning for the top. She was just doing the work. But one day, her supervisor walked in and said, “They want you to lead the department.”

“I thought he meant temporarily,” Jonna told the Spy Museum. “But it was official. Chief of Disguise.” She was the first woman to ever hold the role.

Her response wasn’t a celebration—it was resolve. “If I take it,” she said, “I’m going to run it my way.” Langley didn’t argue. The quiet operator had just become the CIA’s master of deception.

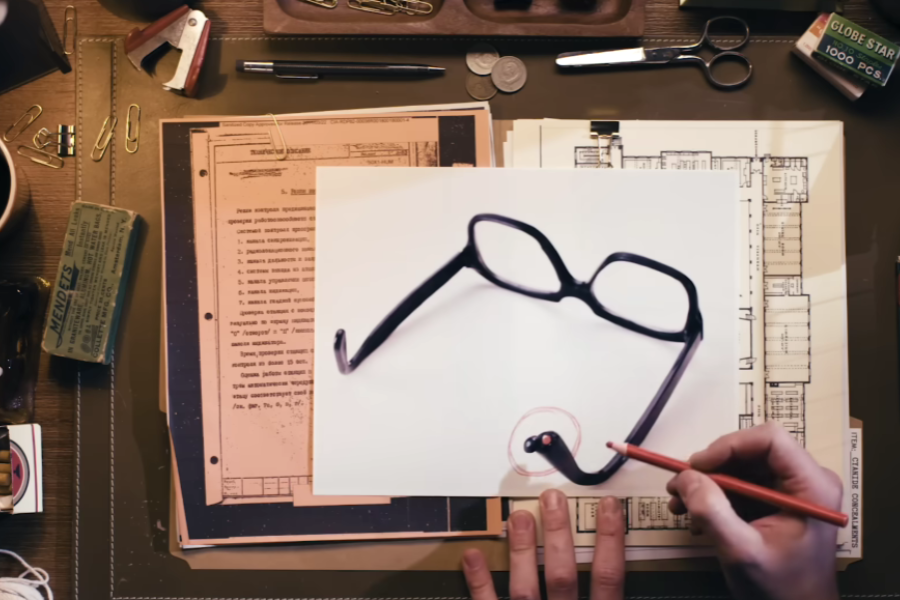

Secrets in Her Pocketbook

Jonna’s disguise kits were masterclasses in misdirection. Lipstick tubes held microfilm. Powder compacts hid flash drives. One earring concealed an antenna. “I weaponized the everyday,” she said at a 2019 panel.

Male operatives had standard kits—watches, briefcases, and ties. Jonna asked, “Why not exploit assumptions about women?” A beaded necklace could contain an escape tool, and a purse could store a disguise.

“People don’t search the things they think are harmless,” she said. Her designs saved lives—and redefined tradecraft. But her real weapon wasn’t lipstick or latex. It was invisibility wielded with intention.

The Power of the Invisible Woman

As Chief, Mendez remained unassuming. She didn’t dress like a boss or speak like one. “And that’s exactly why I got away with things,” she told The Washington Post.

Underestimation became leverage. “They thought I was the secretary,” she recalled with a smile. “That was fine. I used it.” Meetings became information harvests—no one filtered themselves around her.

But behind the quiet presence was surgical skill. “She was always watching, always calculating,” said a former colleague in The Moscow Rules. Her invisibility was a tactic, not a limitation. And it was about to collide with Hollywood.

The “Hollywood” Connection

As disguise tech evolved, so did Jonna’s collaborators. She turned to Hollywood—literally—partnering with special effects experts who worked on films like Mission: Impossible and Planet of the Apes.

“We needed masks that could pass under daylight scrutiny,” she told 60 Minutes. “Not just from ten feet away—but two feet, in motion, under pressure.” Film prosthetics helped bridge the gap.

She wasn’t copying Hollywood. She was challenging it. “They had hours to apply a mask,” she said. “We had seconds.” The result? A new class of disguises—so lifelike they could fool anyone. Even a U.S. president.

Her Greatest Creation

One of Mendez’s proudest tools was a fully wearable mask and disguise ensemble—skin-like, breathable, and deployable in under a minute. “We called it ‘Jack-in-the-Box,’” she explained in The Moscow Rules.

The disguise wasn’t just visual. It transformed posture, gait, and even height. “You could walk out of a car as one person, and back in as someone else,” she said.

It was tested in the field, refined with Hollywood techniques, and ultimately deployed in high-risk zones. But Jonna had her own test in mind—one final demonstration to prove its power at the highest level.

Lies Told with a Smile

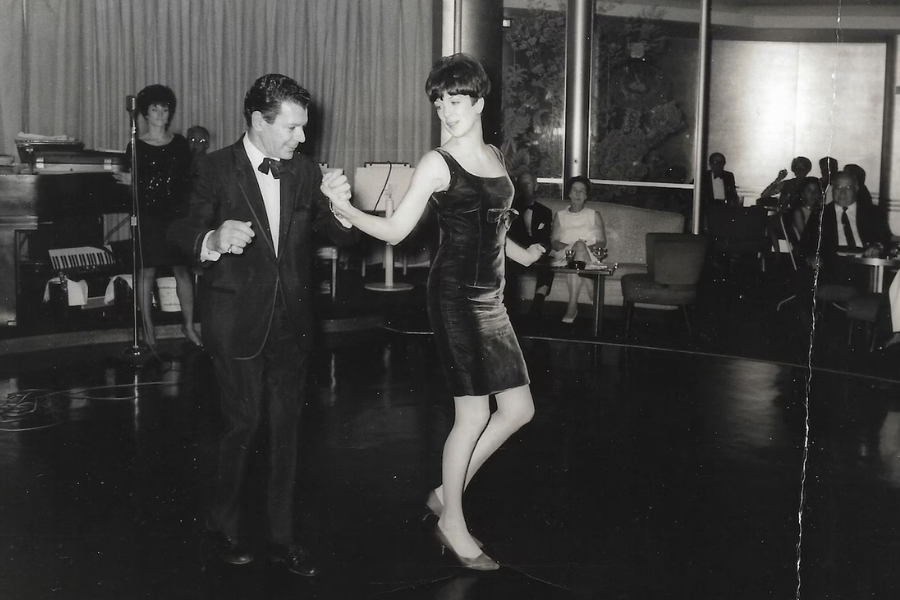

Not all disguises involved latex. Sometimes, it was demeanor. Accent. Confidence. “Your voice is a disguise,” she told CIA recruits. “So is your smile. So is silence.”

In one mission, she posed as a cultural liaison during a reception in Vienna. “I got the diplomat talking,” she told SpyTalk. “He thought he was seducing me. I was extracting intel.”

“I never said a single false word,” she added. “But everything I implied was a lie.” Her charm disarmed targets. Her training outmaneuvered them. In espionage, sincerity is the most dangerous tool of all.

Grooming the Next Ghosts

As Chief of Disguise, Jonna didn’t just innovate—she taught. Young officers arrived at Langley, nervous and idealistic. She met them with clarity: “Fear means you understand the stakes,” she told Spy Museum Live.

She stressed realism over theatrics. “This isn’t Hollywood,” she said. “Your disguise must survive sweat, wind, cameras, and doubt.” Students practiced gestures, eye contact, even how to blink like a local.

“They were scared, and that’s good,” she recalled in a 2020 interview. “Because if they thought it was easy, they’d be dead.” Her lessons stayed with them—in warzones, safehouses, and exits they never spoke of.

The Ethics of Deception

Years after retirement, Mendez confronted the moral toll. “Spying is built on lies,” she admitted during a C-SPAN panel. “You lie to the enemy, to your family, sometimes to yourself.”

One mission haunted her. A source believed she was a journalist. “He trusted me,” she said. “And I used that trust to protect others.” She paused. “He never knew the truth.”

But she made peace with it. “Lying for your country is not noble—it’s necessary,” she told The New Yorker. “But it changes you. Every mask you wear leaves something behind.” Her next loss, though, would be personal.

Losing Tony

Tony Mendez died in January 2019 after a long battle with Parkinson’s. “He was the one person who knew everything about me,” Jonna told The Washington Post. “And I didn’t have to explain.”

Their marriage was built on secrets—but also understanding. “Tony didn’t flinch at silence. He lived in it too,” she said. They shared missions, disguises, and a son born between operations.

At his funeral, she stood quietly near the back. “I didn’t want to be saluted,” she later said. “I just wanted to remember the man who made masks with me.” But the world saw them both now.

Operation Illusion

One operation in Southeast Asia demanded speed, invisibility, and invention. A source needed to be extracted, but surveillance was relentless. “The disguise had to be deployable mid-movement,” Mendez said at a CIA Legacy panel.

She designed what became known as a “pop-up” disguise. The agent entered a public plaza as a delivery worker, ducked briefly behind a statue, and emerged seconds later as a tourist father with a stroller.

“He made it out,” she confirmed in The Moscow Rules. “They never saw it happen.” It was her proudest success—not because it dazzled, but because it worked. And now, the world would start to see.

Declassified at Last

In the 2000s, the CIA began declassifying portions of her work. Jonna could finally speak publicly—not in full, but enough. “I don’t tell secrets,” she told CBS’s This Morning. “I share lessons.”

She began lecturing at universities, intelligence summits, and museums. “There was hunger,” she recalled. “People wanted to know what was real and what was fiction. Usually, it was both.”

What surprised her most? “How few people knew women were doing this work,” she said. “That’s why I’m speaking now.” Her silence had once been patriotic. Now, her voice became its own kind of service.

Hollywood Comes Knocking

After Argo spotlighted Tony’s legacy, filmmakers turned to Jonna. “They wanted the woman in the mask,” she said to Vanity Fair. “I told them, ‘It’s not about flash. It’s about fear.”

She consulted on scripts, corrected errors—like how fast a disguise could be applied or what field agents really carried. “A mask isn’t worn,” she told a producer. “It’s inhabited.”

Still, she didn’t seek fame. “If they make something truthful, I’ll help,” she said. “But I spent 27 years hiding for a reason.” The museums, however, wanted more than words—they wanted her tools.

Legacy in Latex

The Smithsonian and the International Spy Museum both asked to display Jonna’s tools—masks, wigs, and adhesive kits. “Artifacts,” they called them. “Weapons,” she replied during a 2020 SpyCast interview.

One latex face sits behind glass now—lifelike and frozen mid-expression. “It fooled border guards,” she said. “Now it’s just a display. But it still makes me nervous looking at it.”

For Jonna, every disguise held a memory—a city, a risk, a near miss. “People see cleverness,” she told The Washington Post. “I see agents who came home because of what we built.” But not all missions ended clean.

The Disguise That Didn’t Work

It was a routine operation. A field agent used a mask prototype that hadn’t been fully tested. “We were pushing boundaries,” Mendez later admitted. “But we didn’t calibrate for lighting.”

Checkpoint guards hesitated. One guard leaned in too close. “He saw something—maybe a seam, maybe just doubt,” she recalled. “We had to pull the agent out early.” The mission was aborted.

Failure stung, but it taught. “You learn more from a bad disguise than a perfect one,” she told SpyTalk. “You see where the illusion cracks.” That night, she reworked the eye sockets herself.

In Her Own Words

In 2019, Jonna co-authored The Moscow Rules with Tony Mendez and co-writer Bruce Henderson. “It was our way of capturing the craft—before it vanished with us,” she said.

The book is part memoir, part tradecraft manual. “It’s not about bragging,” she told The New York Times. “It’s about showing how intelligence works—and why it matters in a democratic society.”

Readers were drawn not just to the missions, but to the humanity. “People think spies are fearless,” she said. “We’re not. We’re scared all the time. We just learn to move anyway.”

Women of the CIA

When Mendez joined the CIA, women rarely made it past clerical work. “They were called ‘the girls,’ even if they were 45,” she told The Washington Post. “It was baked in.”

But she remembered them all—quiet operatives, surveillance experts, disguise techs—who did the same dangerous work without acknowledgment. “They were invisible twice,” she said. “To the enemy and to their own agency.”

She mentored many of them, opening doors that never existed for her. “I wasn’t blazing a trail,” she said. “I was kicking it open quietly, one hinge at a time.” And others followed.

Dismantling the Myths

Hollywood glamorized the work—fast cars, tuxedos, martinis. Mendez scoffed. “There’s nothing glamorous about sweaty latex and knowing one mistake could get someone killed,” she told NPR’s Fresh Air.

She used her lectures to set the record straight. “Real spies live in a fog of boredom, broken by lightning bolts of terror,” she said. “And then it’s back to waiting.”

Her mission post-retirement? Reality. “If you’re going to admire this work, admire the fear, the grit, the precision,” she said. “Because that’s the real story—not explosions. Just masks and silence.”

The Final Briefing

She didn’t want a ceremony. “Just let me walk out the same way I walked in—quietly,” she said. She handed over her badge and turned toward the parking lot.

Before leaving, she paused outside the disguise lab. “I touched every mask on that wall,” she told SpyCast. “I knew every officer’s life behind them.”

She walked out alone. No applause. No medals. But her impact lingered in every operation still running. “That’s how you know you’ve done your job,” she said. “You leave. But the work doesn’t.”

The Woman Behind the Mask

Today, Jonna Mendez lives without aliases. No safehouses, no flash paper, no burner phones. Just books, lectures, and the occasional visit to the Spy Museum, where ghosts live behind glass.

“I still catch myself checking for exits when I walk into a room,” she told The Atlantic. “It’s instinct now. The tradecraft never leaves you—it just settles into your skin.”

She doesn’t see herself as extraordinary. “I did my job,” she said simply. “And I made sure other people could do theirs—and live to tell no one about it.” But history is telling it now.

The Disguise That Changed History

That day in the Oval Office, 1993, was brief. Ten seconds. A demonstration. A mask peeled away. President George H.W. Bush leaned forward and said, “This is what we can do?”

Jonna Mendez nodded. “Yes, sir.” CIA Director James Woolsey later confirmed the moment. “It shocked him,” Woolsey said. “That’s what we wanted. If we could fool you, we could fool anyone.”

That mask changed policy. It was a solid proof that the CIA could smuggle an operative through hostile territory, undetected—even under a head of state’s nose. It secured funding. And it immortalized Jonna, proof that invisibility is a craft. And she was its master.